Why Uncertainty Gets Priced In, Not Talked Away

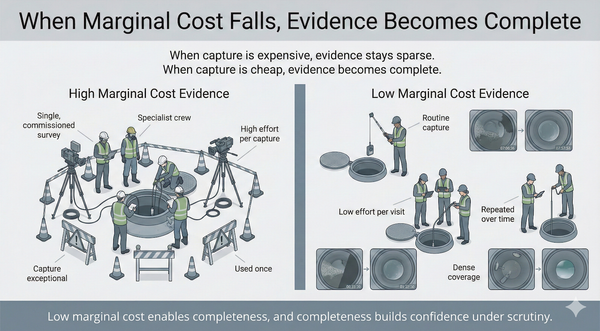

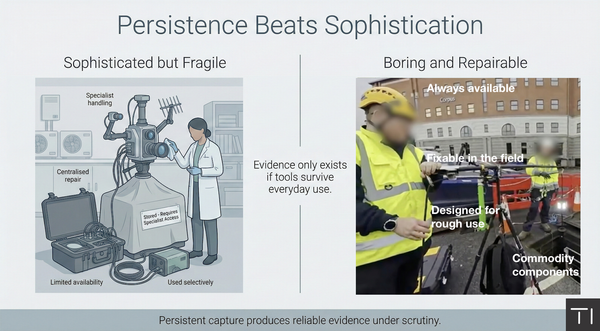

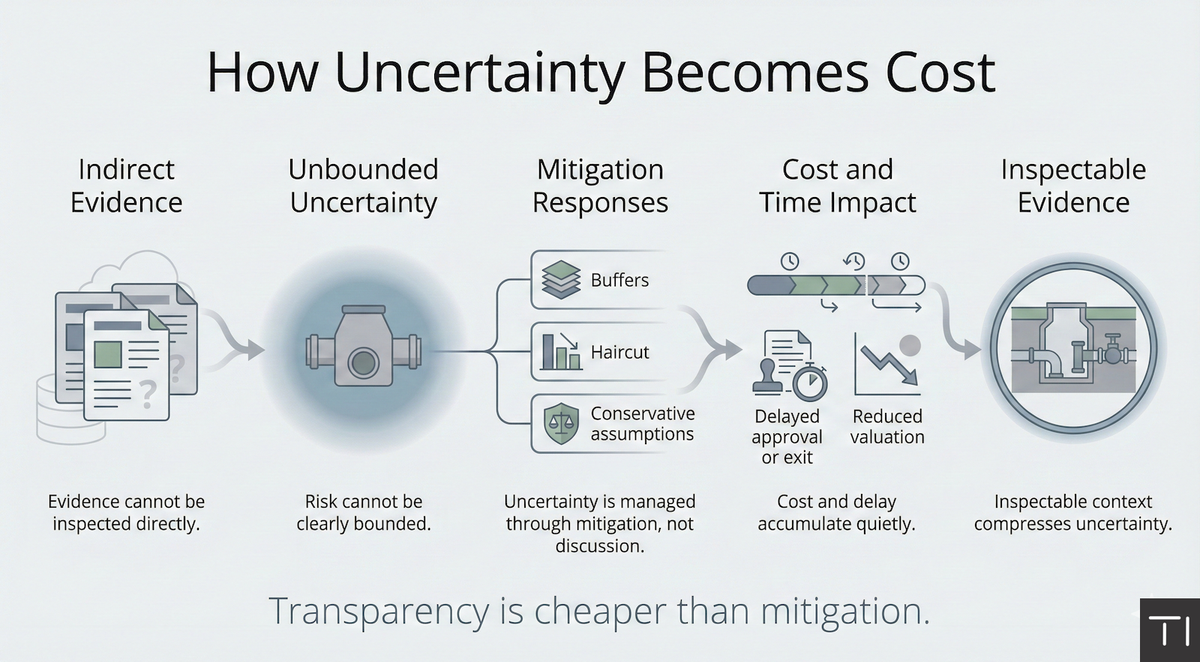

In infrastructure ownership and finance, uncertainty is rarely debated at length. It is priced. When evidence is incomplete, indirect, or difficult to inspect, the response is not extended discussion but adjustment. Buffers increase, assumptions become more conservative, and value is discounted to protect against what cannot be clearly seen.

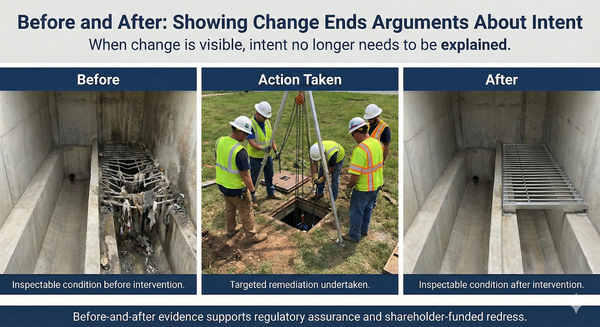

This dynamic is often misunderstood by operators. From inside an organisation, the asset may feel well managed. Issues are known, workarounds exist, and experienced staff understand where the real risks lie. From outside, particularly during due diligence or refinancing, that confidence carries little weight unless it can be substantiated through evidence that survives scrutiny.

Buffers are the most immediate expression of this. When reviewers cannot bound uncertainty, they assume worst-case scenarios. Cost contingencies widen. Maintenance allowances increase. Capital requirements are brought forward. Each adjustment is individually defensible, but together they inflate the perceived burden of ownership.

Haircuts follow the same logic. Valuation models respond to uncertainty by discounting future cash flows or increasing risk premiums. This is not a judgement on competence. It is a rational response to information asymmetry. If the true condition, configuration, or adaptability of assets cannot be inspected directly, the safest position is to assume downside.

Conservative assumptions compound the effect. Where evidence is thin, reviewers default to cautious interpretations of capacity, resilience, and remaining life. These assumptions then propagate through regulatory submissions, investment plans, and financial models. Once embedded, they are difficult to unwind, even if later evidence suggests they were overly pessimistic.

The consequences extend beyond valuation. Delayed exits are a common outcome of unresolved uncertainty. Transactions slow as additional surveys are commissioned, further reviews are requested, or confidence takes longer to build. In some cases, deals proceed on less favourable terms. In others, they are postponed entirely until evidence gaps can be closed.

What is striking is that none of this behaviour is adversarial. Investors, lenders, and regulators are not trying to extract value unfairly. They are responding to risk they cannot otherwise resolve. When uncertainty persists, mitigation becomes the default strategy. And mitigation is expensive.

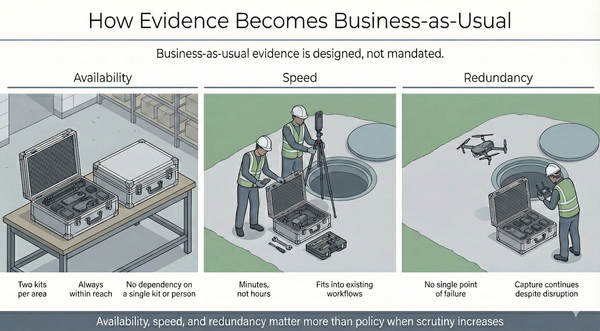

This is why transparency is cheaper than mitigation. Providing inspectable, revisitable evidence early reduces the need for buffers, haircuts, and conservative assumptions later. It allows uncertainty to be bounded rather than imagined. Even when risks remain, they can be discussed explicitly rather than priced implicitly.

Attempts to talk uncertainty away rarely succeed. Verbal assurances, historic performance, or statements of intent do little to change risk perception when evidence is indirect. Under scrutiny, confidence without transparency is treated as optimism. Transparency, by contrast, allows others to form their own judgement, which is ultimately more persuasive.

For asset owners, the implication is pragmatic. Investment in evidence quality is not an overhead incurred for compliance or reassurance. It is a way of reducing the structural costs imposed by uncertainty. Where evidence can be inspected, challenged, and revisited, risk premiums shrink. Where it cannot, they grow.

Uncertainty will never disappear entirely. Infrastructure assets are complex, long-lived, and exposed to changing conditions. But the way uncertainty is handled matters. When it is left unresolved, it is priced in. When it is addressed through transparency, it becomes cheaper to manage.