Why the Best Evidence Tools Are Boring and Repairable

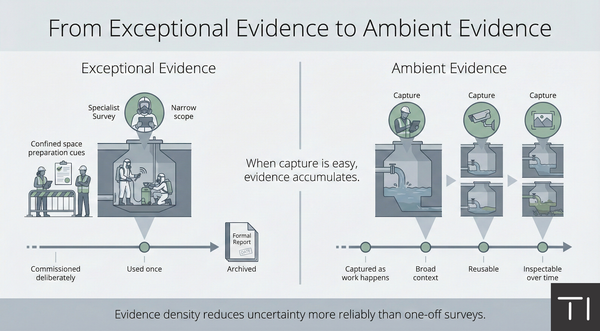

In regulated infrastructure, the tools used to gather evidence often attract more attention than the evidence itself. There is a persistent assumption that “enterprise-grade” capability must be complex, specialised, and tightly controlled. In practice, this assumption frequently produces systems that are impressive on paper and fragile in the field.

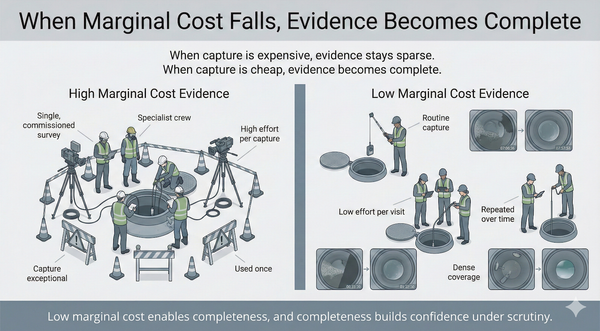

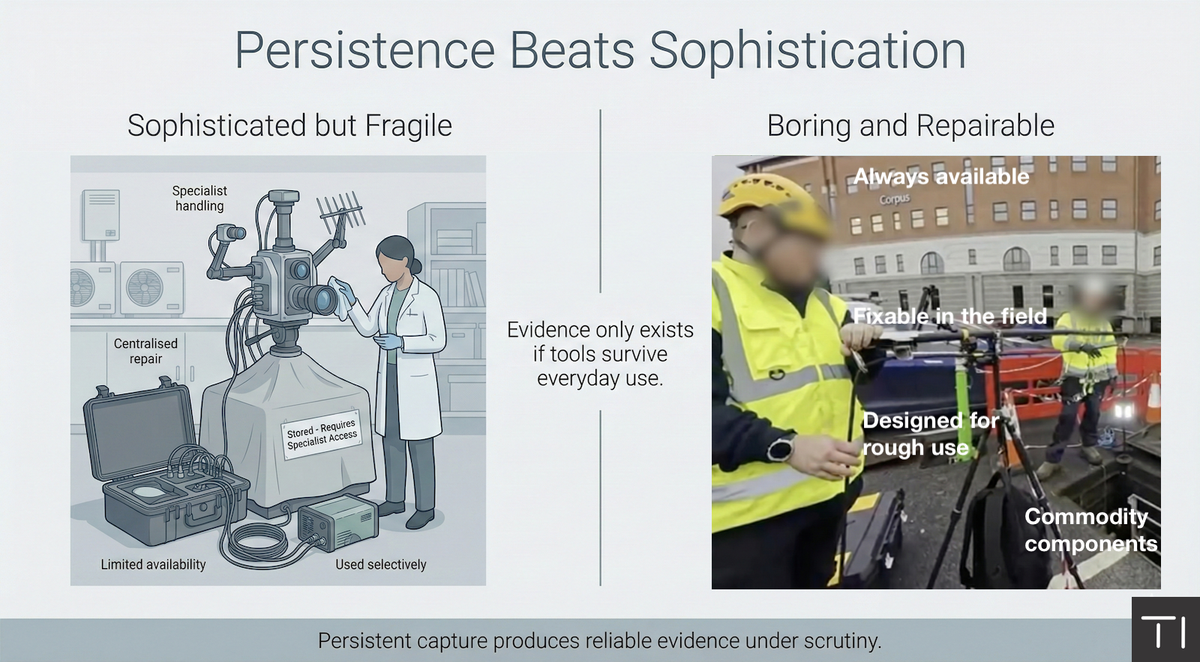

What matters most for evidence is not sophistication, but persistence. Evidence that is captured once and then fails to be repeated, repaired, or reused has limited value under scrutiny. Evidence that accumulates steadily over time, across many visits and many people, becomes robust precisely because it endures.

This is why the most effective evidence tools in operational environments tend to be boring. They are simple to understand, easy to use, and designed to survive being knocked around. They rely on commodity components that can be replaced quickly, not bespoke parts that require escalation or downtime. When something breaks, it can be fixed in the field rather than taken out of service.

Prosumer-grade equipment exemplifies this. Tools designed for extreme sports enthusiasts, outdoor use, or fieldwork are built to tolerate water, dirt, vibration, and impact. They prioritise battery life, reliability, and ease of replacement. They assume rough handling and intermittent charging. These characteristics map far more closely to operational reality than the delicate expectations of many enterprise systems.

The alternative is familiar. Highly specified equipment that requires careful handling, specialist training, and controlled environments quickly becomes scarce in practice. It sits in cupboards because teams are reluctant to risk damaging it. When it does fail, it is removed from service until it can be repaired centrally. Evidence capture becomes exceptional again, dependent on the availability of the “right” kit and the “right” people.

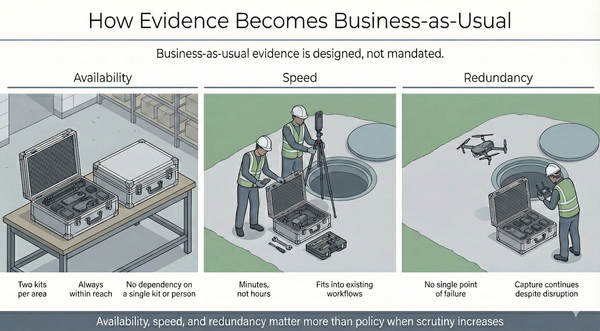

Repairability is therefore a governance feature, not a technical detail. Tools that can be fixed with readily available parts, such as tripods, cords, or carabiners sourced from any hardware supplier, reduce dependency and delay. They keep evidence flowing even when conditions are imperfect. Over time, this reliability matters more than marginal gains in precision.

The same logic applies to power and logistics. Equipment that lasts a full day on a single charge and can be topped up anywhere fits naturally into existing workflows. Equipment that requires careful power management or dedicated infrastructure introduces friction. Friction reduces use. Reduced use reduces evidence density.

From a governance perspective, fragile systems create silent failure modes. Capture is intended, but does not happen because the kit was unavailable, broken, or inconvenient. These gaps are only discovered later, under scrutiny, when the absence of evidence becomes a problem. Robust, boring systems fail loudly and visibly, and are therefore fixed quickly.

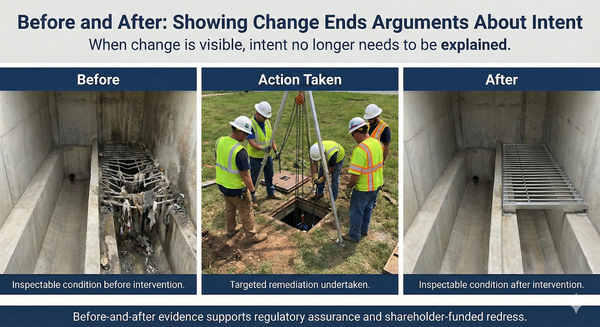

This does not mean that sophistication has no place. Advanced analysis, modelling, and integration remain essential. The point is that the foundation of any evidence regime must be reliable capture. Without persistent input, even the most advanced downstream systems are starved of reality.

The myth that enterprise capability requires fragility is particularly unhelpful in regulated environments. Regulators, boards, and investors care less about how impressive a system appears and more about whether evidence exists when it is needed. Persistence, repairability, and ubiquity support that outcome far more effectively than complexity.

In the current regulatory climate, where evidence must withstand repeated inspection and challenge, the safest tools are those that people actually use. Boring, repairable equipment lowers the barrier to routine capture. Routine capture produces dense, revisitable evidence. And dense evidence, accumulated quietly over time, is what ultimately survives scrutiny.

Persistence beats sophistication because evidence that exists is always more valuable than evidence that might have existed if conditions had been perfect.