Why Some Evidence Feels Obvious the Moment You Look at It

Experienced water industry professionals often make confident judgements very quickly when they are presented with rich site context. They do not work through a checklist or calculate their way to a conclusion. They recognise patterns. This is not intuition in the casual sense, but the result of years spent seeing how assets are actually built, how they age, and how they behave under real operating conditions.

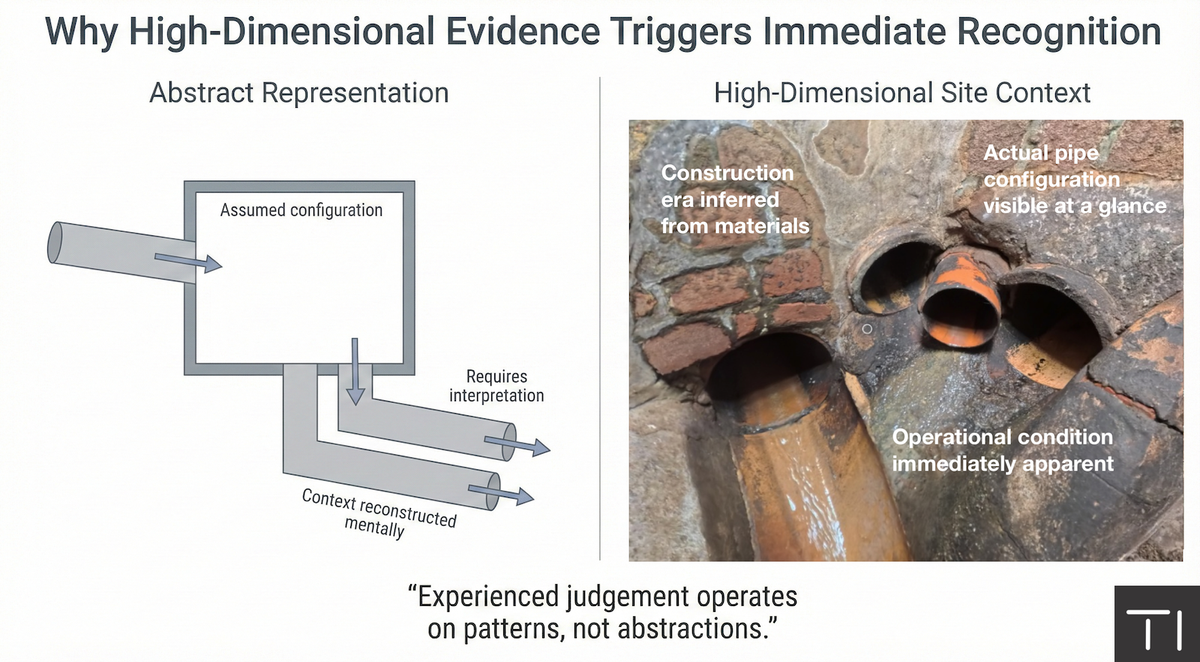

That kind of judgement is hard to trigger with abstract data alone. Tables, models, and records require translation back into a mental picture of the site. Even when the data is accurate, that reconstruction takes time and effort. Experienced practitioners frequently ask to visit a site not because they distrust the data, but because they need to see how the pieces fit together in physical space.

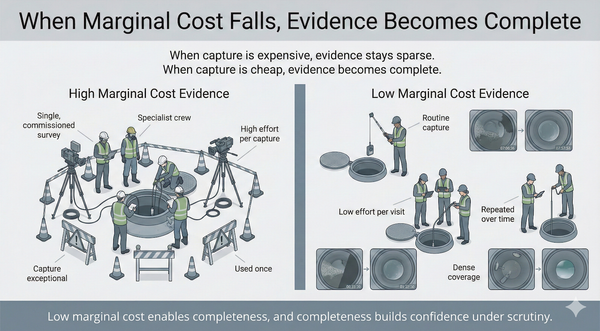

High-dimensional visual evidence such as 360° high resolution imagery or overhead drone images changes this dynamic. When people who know the network well are shown spatially rich site context, recognition is often immediate. Multiple variables are processed at once, without conscious effort, and conclusions form quickly because the evidence aligns directly with how expertise is built.

Consider a combined sewer overflow that appears in GIS as a chamber with one inlet and two outlets. On paper, this looks straightforward. In reality, a glance at a full 360° view of the chamber makes it immediately obvious that there are six pipes, not three. Some are partially obscured, some enter at unexpected angles, and some are legacy connections no longer shown in records. No one needs to be convinced. The discrepancy is visible, and its implications for capacity, maintenance, and future modification are instantly understood.

The same applies to operational condition. A dry pipe, one that has not conveyed flow for some time, is immediately apparent to experienced eyes. Discolouration, debris patterns, and surface condition tell a clear story. This is not something that needs to be measured or modelled before it is recognised. It is seen, and the judgement follows. Trying to infer the same conclusion from historic flow data or maintenance logs is possible, but slower and less certain.

Construction detail provides another example. The materials used, the brickwork pattern, the jointing, and the overall form of a chamber quickly signal when it was built and under what assumptions. Experienced practitioners can tell at a glance whether an asset dates from a period of lower population density, different rainfall expectations, or older design standards. That contextual understanding immediately shapes expectations about resilience, headroom, and suitability for upgrade. Again, this is not guesswork. It is pattern recognition grounded in long exposure to similar assets.

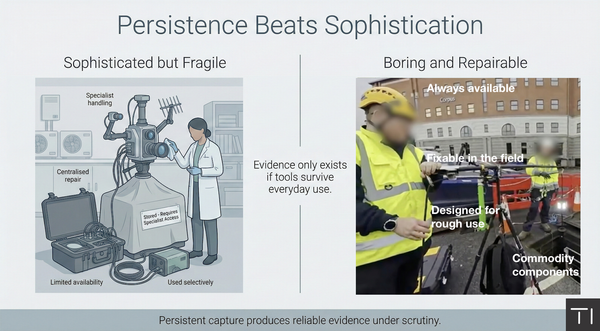

What matters here is not that these judgements are fast, but that they are holistic. High-dimensional evidence allows many cues to be taken in simultaneously. Congestion, clearance, access difficulty, condition, and constructability are all assessed together. This is why the judgement feels obvious. Not because the situation is simple, but because the evidence is complete enough to engage the expertise properly.

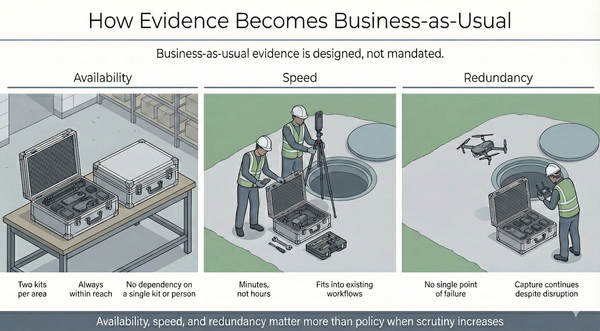

This has direct implications for DWMP development and option selection. When early decisions are made on abstract representations alone, experienced reviewers often hesitate. They sense that something is missing, even if they cannot immediately articulate what it is. When the same decisions are supported by rich, observable site context, that hesitation often disappears. Options are screened more confidently, and weak assumptions are identified earlier.

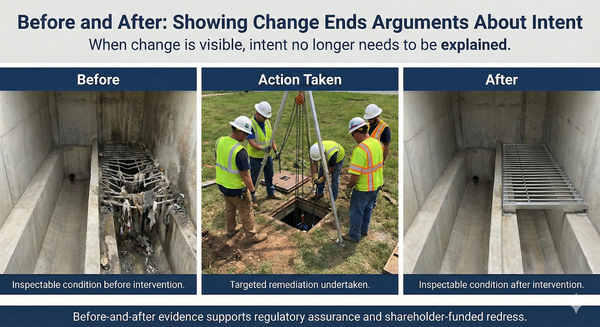

There is also an important social dimension. Experts are often able to see problems quickly, but struggle to explain them succinctly to others. When colleagues, contractors, or regulators can see the same evidence, explanation becomes less necessary. Shared visibility aligns judgement across roles, reducing debate driven by interpretation rather than reality.

None of this diminishes the value of models, records, or analysis. Those remain essential. What high-dimensional evidence does is anchor them. It gives experienced practitioners the context they need to apply their judgement effectively, and it allows that judgement to be shared rather than held in someone’s head.

For governance and assurance, this matters more than it might first appear. Evidence that supports rapid, confident expert judgement is easier to defend than evidence that requires repeated translation. It reduces the need for repeated site visits, long explanatory chains, and defensive documentation. Decisions feel more solid because they are grounded in something that can be seen and revisited.

The value of high-dimensional evidence is therefore not just technical. It aligns with how expertise actually works in the water industry. When people who know the system can see it properly, they recognise what matters almost immediately. That recognition is not a shortcut around rigour. It is a sign that the evidence is finally speaking the same language as the experience used to interpret it.