Why Ofwat Is Rejecting Remediation Spend Without Root-Cause Evidence

Ofwat’s recent decisions to reject or challenge remediation funding requests have surprised some in the sector. From the utility perspective, proposed interventions often feel reasonable, urgent, and well intentioned. Assets are ageing, performance is under pressure, and remediation appears necessary. From the regulator’s perspective, however, a different question is being asked: what problem is this spend actually fixing, and how do we know?

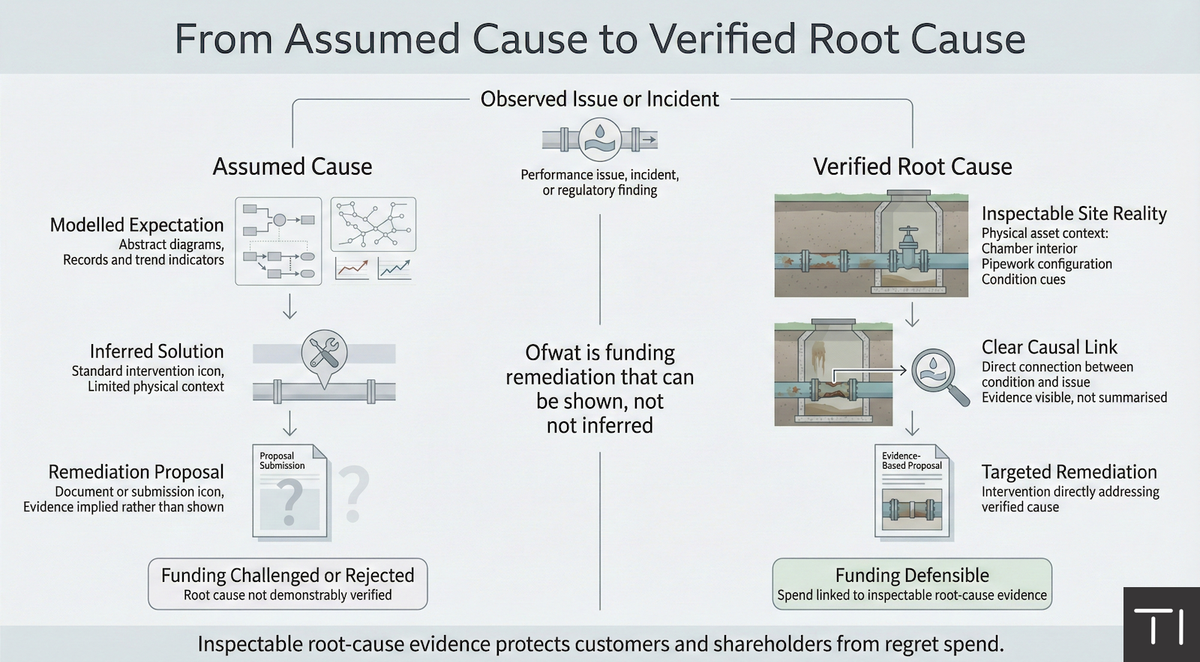

This is where the concept of “regret spend” becomes central. Regret spend is not waste in the obvious sense. It refers to expenditure that, with better evidence, would either not have been required at all or would have been targeted differently. Ofwat’s stance is not that remediation is unnecessary, but that remediation must be demonstrably linked to verified root causes rather than inferred or assumed ones.

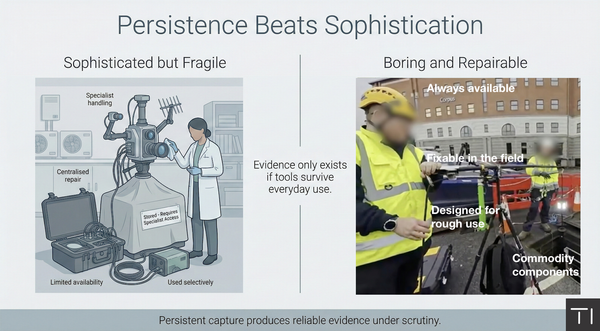

Assumed causes are fragile under scrutiny. In many cases, proposed solutions are based on patterns seen elsewhere, modelled expectations, or historic understanding of how assets should behave. These inputs are useful, but they are not evidence of what is actually happening at a specific site. When funding requests rely on this kind of abstraction, the regulator is left being asked to accept a narrative rather than inspect a problem.

Under enforcement conditions, that is no longer sufficient. Ofwat is increasingly explicit that companies should already understand the assets they are responsible for maintaining. Where remediation is proposed to address issues that routine maintenance funding was intended to cover, the burden of proof shifts. The regulator expects companies to show, not assert, that the root cause was unknown, unavoidable, or genuinely outside previous funding assumptions.

This is why remediation proposals built on assumed causes struggle. When evidence cannot demonstrate, for example, that a pollution incident was driven by an unmapped connection, a missing screen, or an unexpected configuration, the regulator defaults to scepticism. The question becomes whether the spend represents genuine remediation or a retrospective correction of incomplete asset understanding.

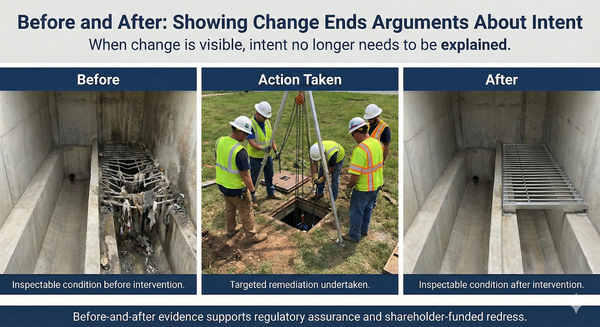

Inspectable reality changes this conversation. When companies can demonstrate, through observable site evidence, that a problem arose from conditions that were not visible or knowable through normal records, the case for remediation strengthens materially. Root causes can be shown directly. Assumptions can be tested. The regulator can see why the issue was not previously addressed and why the proposed intervention is appropriate.

This matters for capital efficiency. Remediation spend that targets verified root causes is more likely to resolve the underlying issue and less likely to require follow-on interventions. Spend based on assumptions often addresses symptoms instead. When those assumptions prove incomplete, additional work is required, increasing cost and eroding confidence in future plans.

It also matters for shareholder-funded redress. Where companies are required to fund remediation from shareholder resources rather than customer bills, scrutiny intensifies further. Boards and investors need confidence that redress spend is necessary, proportionate, and effective. Inspectable evidence provides that confidence. It allows shareholders to see what is being fixed and why, rather than relying on assurances that a problem existed.

Ofwat’s position is therefore not punitive. It is protective. By rejecting remediation spend that cannot be tied to clear root-cause evidence, the regulator is signalling that capital should not be deployed on the basis of inference alone. This protects customers from paying twice for the same maintenance and protects shareholders from funding interventions that may not address the real problem.

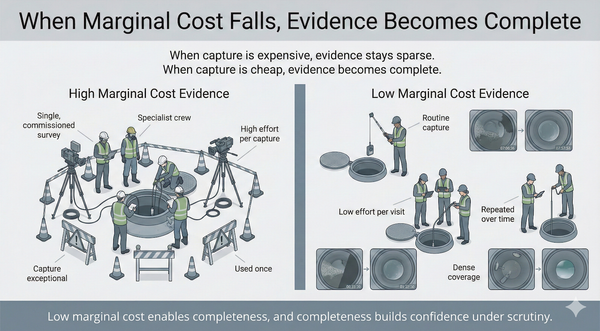

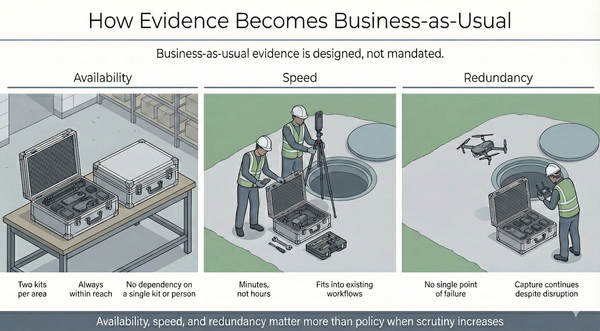

The implication for utilities is pragmatic. Preventing regret spend requires shifting when and how evidence is gathered. Root causes need to be identified early, using evidence that can be inspected and revisited, before remediation plans are finalised. When remediation is grounded in observable reality, funding requests become easier to defend, delivery becomes more focused, and the risk of rejection diminishes.

In the current regulatory environment, the safest way to protect both customers and shareholders is not to argue harder for funding, but to show more clearly what is actually wrong. Ofwat is no longer accepting “this is what we believe the problem is.” It is asking to see it.