Why Evidence Quality Affects Asset Value More Than Asset Age

In infrastructure valuation, asset age is often treated as a shorthand for risk. Older assets are assumed to be closer to failure, more expensive to maintain, and less adaptable to future requirements. Age is easy to record, easy to compare, and easy to model. As a result, it features prominently in valuation discussions, due diligence summaries, and risk registers.

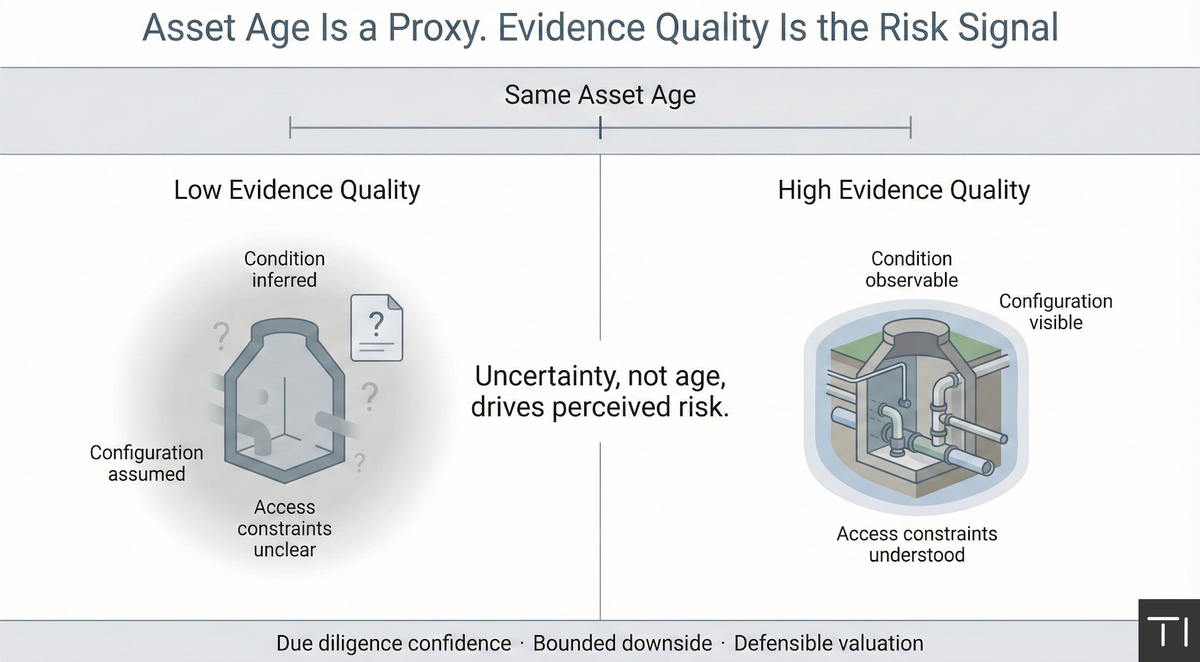

In practice, age is only a proxy. What actually drives risk, and therefore value, is how well an asset is understood.

Two assets of the same age can carry radically different risk profiles. One may be well maintained, accessible, and straightforward to intervene in. The other may be congested, degraded, and constrained in ways that are not visible in records or models. On paper, they look similar. In reality, their future cost, flexibility, and regulatory exposure are very different.

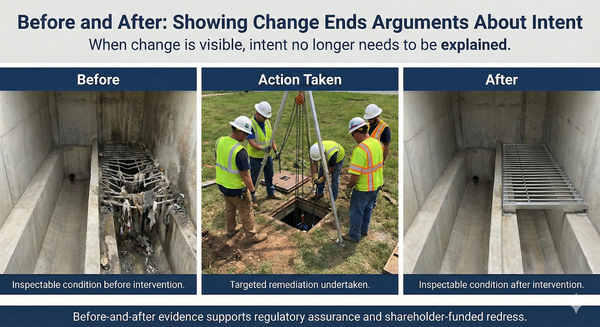

This difference becomes visible when evidence quality is tested. Assets supported by clear, inspectable evidence tend to inspire confidence, even when they are old. Assets supported only by summaries, assumptions, or historic reports attract scepticism, even when they are relatively young. The distinction is not about optimism or pessimism. It is about how much uncertainty remains once the evidence is examined.

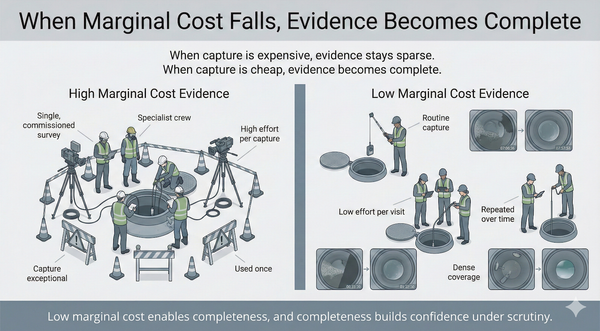

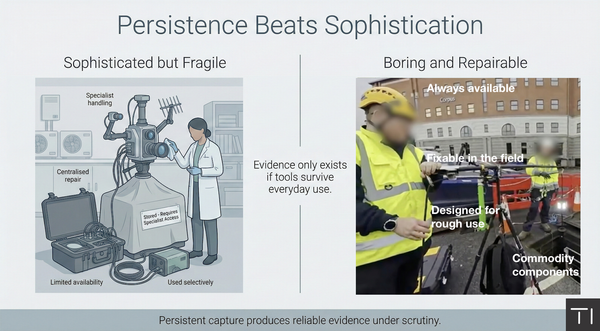

Poor evidence inflates perceived downside. When condition, access, or configuration cannot be inspected directly, reviewers and investors respond conservatively. Buffers increase. Contingencies widen. Discount rates creep up. This is a rational response to uncertainty, not a judgement on management capability. In the absence of reliable context, the safest assumption is that hidden problems exist.

Observable context compresses uncertainty. When evidence allows reviewers to see how assets are actually arranged, how they have aged, and how interventions would be carried out, many questions resolve quickly. Unknowns become knowns. Risks can be bounded rather than imagined. The result is not necessarily a higher valuation, but a more defensible one.

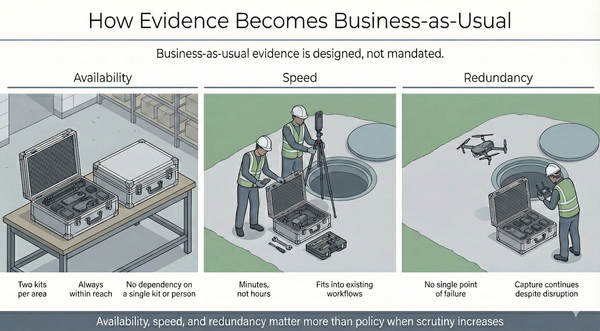

This effect is particularly pronounced during due diligence, refinancing, or regulatory review. At those moments, asset value is tested under time pressure and adversarial questioning. Evidence that relies on explanation or interpretation tends to weaken under scrutiny. Evidence that can be inspected, revisited, and understood directly tends to hold up. The difference shows up in valuation adjustments, not in debate.

It is also important to recognise that asset age does not capture future exposure. Regulatory expectations, climate assumptions, and service standards evolve. An asset that is well understood today is easier to adapt tomorrow. An asset that is poorly evidenced becomes a source of latent risk as expectations change. In this sense, evidence quality is forward-looking, while age is backward-looking.

None of this suggests that age is irrelevant. It remains an important indicator. But it should not be confused with understanding. Age tells you how long an asset has existed. Evidence quality tells you how confident you can be about what it will demand in the future.

For owners, investors, and regulators alike, the implication is subtle but significant. Asset value depends less on how old something is, and more on how well its reality can be inspected and defended. Summaries and averages may be sufficient for reporting, but they are weak foundations for valuation under scrutiny.

In the end, valuation is not just an accounting exercise. It is an assessment of uncertainty. Assets supported by strong, observable evidence carry less of it. Assets supported only by abstractions carry more. Age may signal where to look, but evidence quality determines what is actually found.