Why Early Evidence Reduces Late-Stage Delivery Risk

In many infrastructure programmes, delivery risk appears to emerge late. Scope changes surface during detailed design, costs increase during construction planning, and schedules slip as constraints become clearer. These outcomes are often treated as unfortunate but unavoidable. In practice, they are frequently the result of decisions made much earlier, when evidence was incomplete or overly abstract.

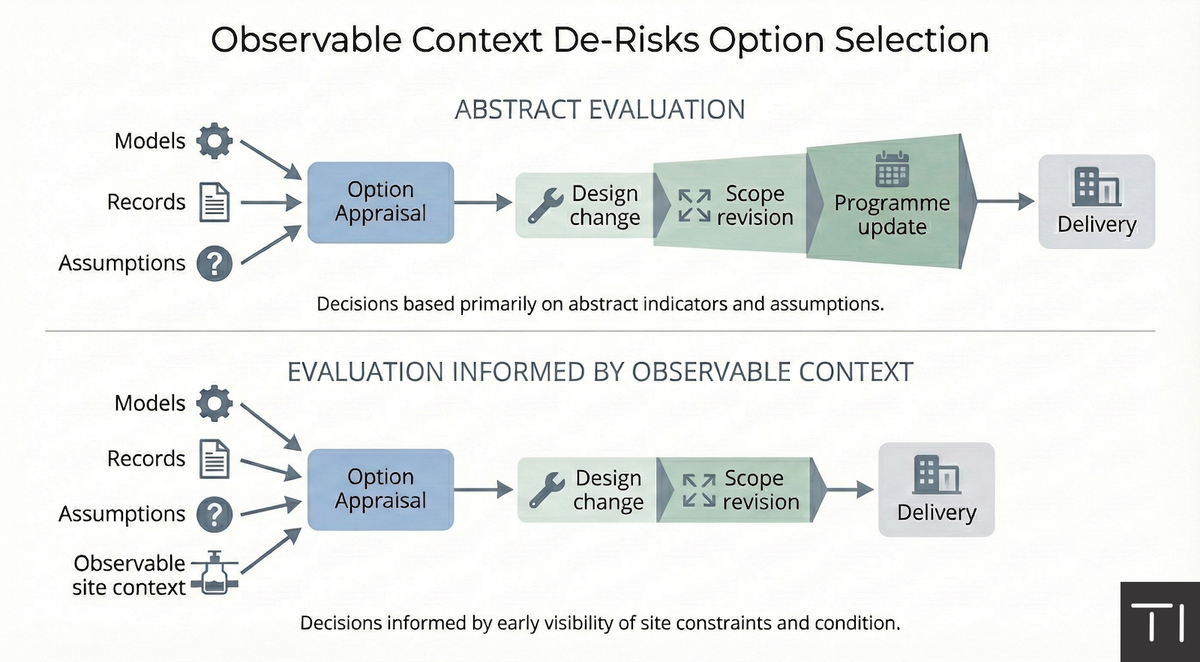

Early assumptions tend to harden into constraints. During Drainage and Wastewater Management Plan (DWMP) development and option selection, teams make reasonable judgements based on the information available at the time. Models, records, and high-level assessments provide direction, but they rarely capture the full set of physical constraints that will shape delivery. Once an option is selected, those early assumptions become embedded in cost estimates, programmes, and approvals, even if they have not been fully tested against site reality.

Evidence gaps often surface when change is most expensive. As projects move toward detailed design and construction planning, questions arise about access, clearance, condition, and constructability. When these questions cannot be answered confidently from existing evidence, teams are forced to revisit earlier decisions. At this stage, options are fewer, commitments are higher, and flexibility is reduced. What could have been a minor adjustment earlier becomes a significant redesign or delay.

Observable site context helps to de-risk option selection. When teams can see how assets are arranged, how space is constrained, and how condition presents in the field, they are better placed to assess feasibility at the outset. This does not remove uncertainty, but it narrows it. Options that look attractive in abstract can be screened out earlier, while those that align with physical reality can be developed with greater confidence.

Early visibility improves cost and schedule confidence. Estimates based on clearer understanding of site conditions are less likely to rely on broad contingencies to cover unknowns. Programmes can be planned around known access constraints rather than optimistic assumptions. This leads to cost profiles and schedules that are more stable as projects progress, reducing the need for late-stage adjustment.

Late-stage surprises are rarely truly unexpected. They are often the predictable outcome of limited early evidence. Congested chambers, restricted access, or unforeseen condition issues do not appear suddenly; they were always present, but not visible at the point when key decisions were made. When evidence is abstracted away from physical reality, these issues remain hidden until they can no longer be ignored.

Better early evidence also affects how risk is priced. When uncertainty is high, contingencies increase to protect against unknowns. This inflation is rational, but it ties up capital and can make options appear less attractive than they would be with clearer evidence. By reducing uncertainty earlier, programmes can carry more proportionate contingencies, improving capital efficiency without increasing risk.

From a procurement and programme management perspective, the implication is straightforward. Evidence quality influences delivery outcomes. Capabilities that provide access to observable site context earlier in the planning process can reduce downstream cost, scope instability, and delay. This is not about eliminating change, but about ensuring that change reflects genuinely new information rather than the late discovery of what could have been seen sooner.

In DWMP delivery, the timing of evidence matters as much as its existence. When teams have access to reliable, reusable site context early, decisions are made with a clearer view of what delivery will actually involve. The result is not perfect certainty, but fewer late-stage surprises and a more resilient path from planning to delivery.