Why Boards Need Inspectable Evidence, Not Performance Summaries

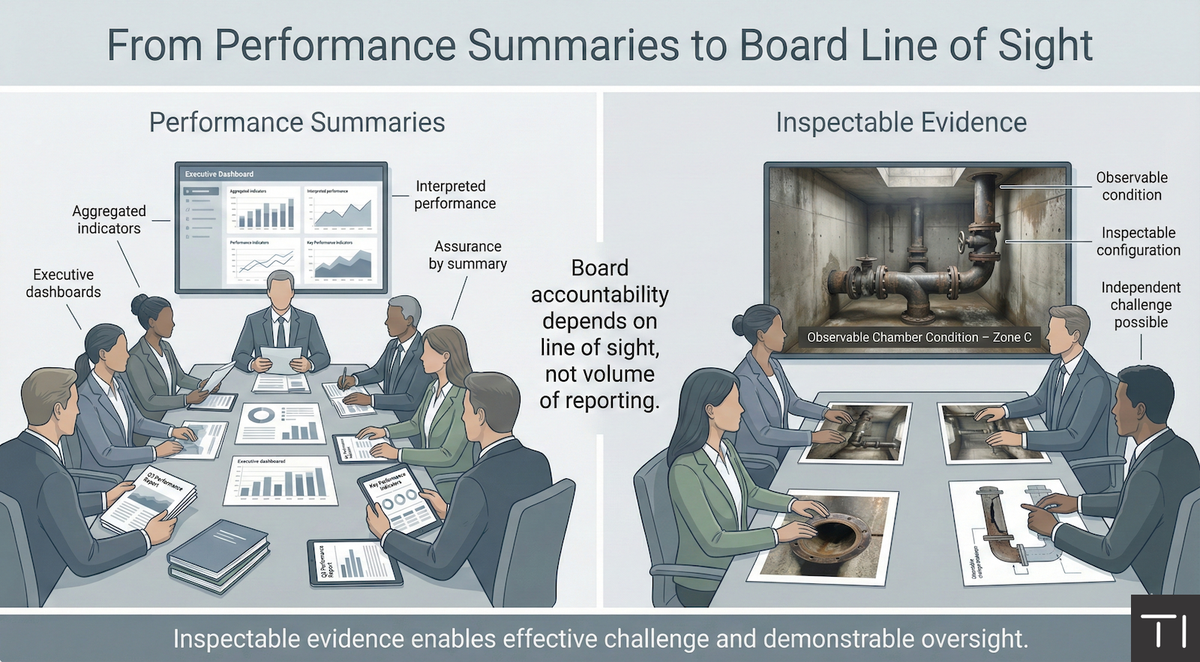

Ofwat’s recent enforcement activity has placed boards firmly in scope. The issue is not whether boards received reports, dashboards, or assurances. It is whether they had genuine line of sight into asset condition and performance, sufficient to challenge assumptions and satisfy themselves that risks were understood and controlled.

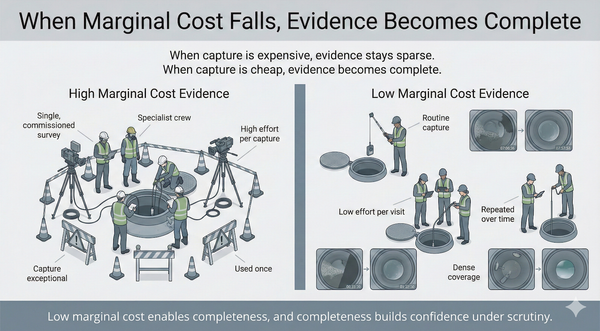

Performance summaries are not inherently flawed. They are necessary to condense complex systems into something manageable at board level. However, summaries are interpretations. They reflect what management believes is happening, filtered through models, metrics, and aggregation. Under regulatory scrutiny, that layer of interpretation is precisely what gets tested.

Board accountability depends on more than receiving information. It depends on the ability to interrogate it. When evidence cannot be inspected independently, challenge is constrained. Questions become circular, and confidence relies heavily on trust in process rather than visibility into reality. This is where boards become exposed, even when management intent and effort are strong.

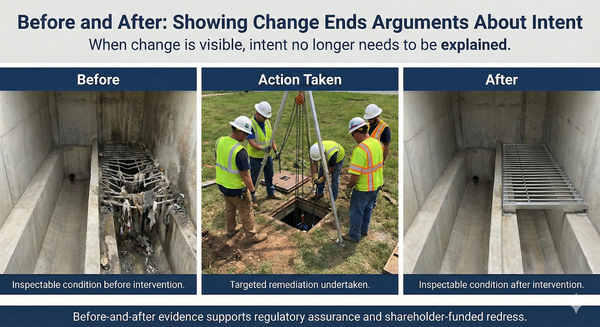

Inspectable evidence changes the nature of oversight. When boards can see, even selectively, the physical context behind key risks and remediation plans, discussions shift. Assumptions can be tested against observable conditions rather than defended abstractly. This does not require boards to become engineers. It allows them to exercise governance through informed challenge rather than reliance on assurance alone.

The distinction is subtle but important. Line of sight is not about volume of information. It is about transparency into what matters. For example, being able to inspect the configuration and condition of a problematic asset provides more grounding than multiple slides summarising performance indicators. The former supports judgement. The latter requires acceptance.

This is also why high-dimensional visual context resonates so strongly with experienced professionals. Rich site evidence allows multiple factors to be assessed simultaneously: access constraints, congestion, condition, and constructability. For boards, this kind of evidence provides confidence that management’s narrative aligns with physical reality, without requiring deep technical interpretation.

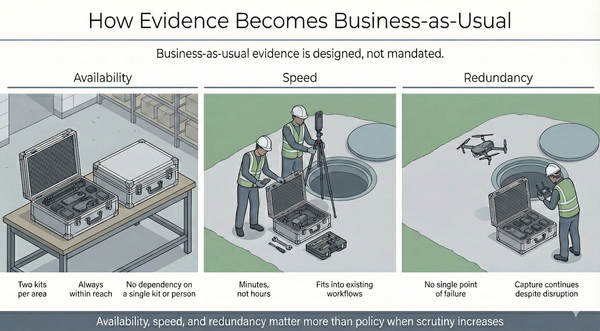

Ofwat’s focus on board oversight reflects an expectation that governance extends beyond process compliance. Boards are expected to challenge, not just receive. That challenge is only effective when evidence is inspectable and revisitable, rather than consumed once in a meeting and then archived.

Framing 360-degree site context as an operational tool understates its governance value. Used selectively, it becomes a mechanism for independent inspection. It allows boards to satisfy themselves that remediation plans target verified issues, that risks are understood at source, and that confidence is grounded in reality rather than inference.

This approach also strengthens the board’s position externally. When regulators, auditors, or other stakeholders ask how oversight was exercised, boards can point to evidence that was available for inspection, not just summaries that were reviewed. This materially reduces exposure, particularly under enforcement or review.

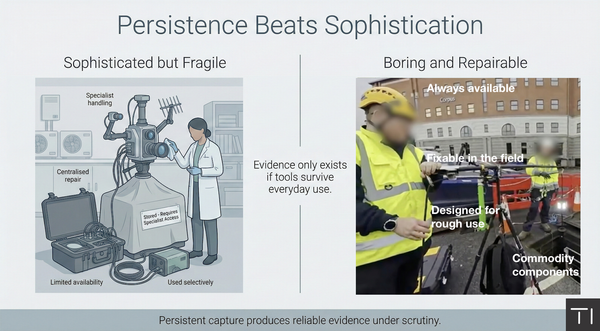

Ultimately, board accountability is not about knowing everything. It is about knowing enough to challenge effectively. Inspectable evidence supports that role. Performance summaries will always have a place, but they are not sufficient on their own. Where regulatory expectations now extend to demonstrable oversight, boards need access to evidence that can be seen, questioned, and revisited.

In the current regulatory environment, governance without inspectability is fragile. Boards that close that gap strengthen not only compliance, but confidence in their ability to steer through scrutiny.