When Evidence Becomes Ambient, Not Exceptional

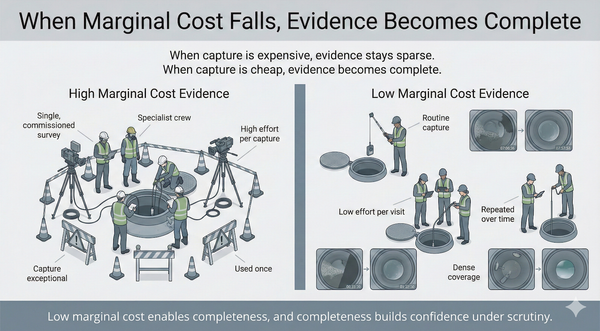

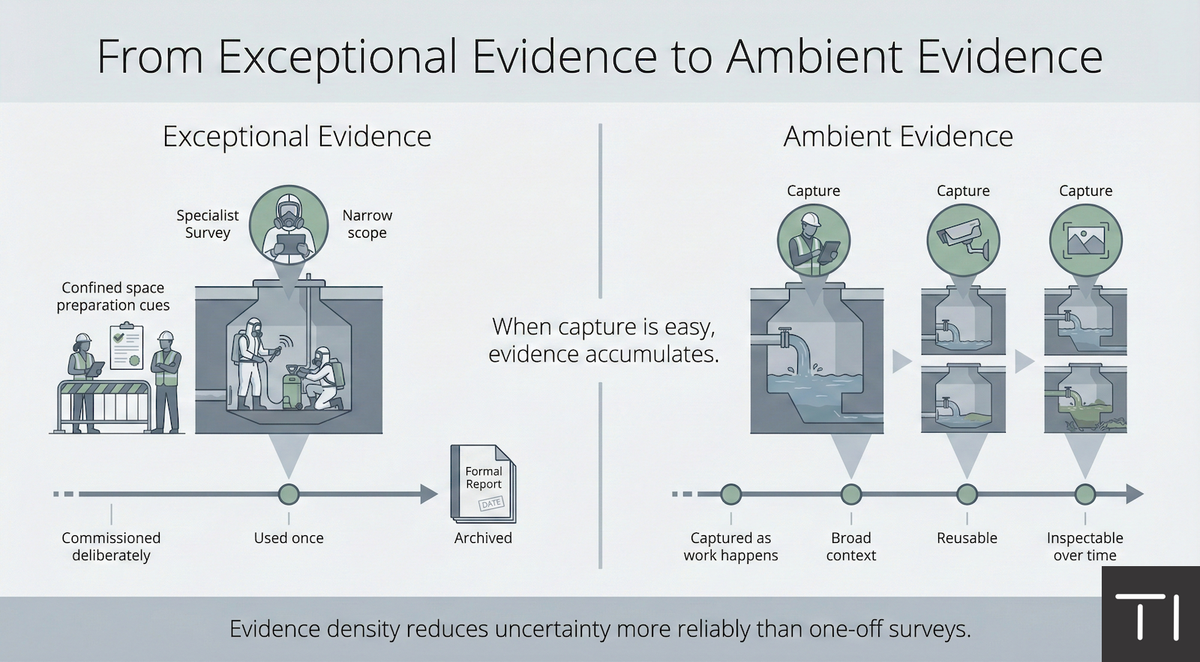

In much of the UK water sector, evidence is still treated as something exceptional. It is commissioned deliberately, planned in advance, and gathered for a specific purpose. Surveys are scheduled. Specialists are mobilised. Access is arranged. Evidence is produced, used, and then archived. This model made sense when capture was costly, disruptive, and risky.

That context has changed. What has not yet changed everywhere is the operating assumption.

When capture becomes fast, robust, and inexpensive, evidence no longer needs to be exceptional. It can become ambient. It accumulates naturally as work happens, rather than being summoned under pressure. This shift has far-reaching consequences for how assets are understood, governed, and defended under scrutiny.

The difference is not subtle. Commissioned evidence is sparse by design. It is optimised to answer a narrow question at a particular moment in time. Ambient evidence is dense. It captures many moments, many perspectives, and many small changes that would never justify a dedicated survey on their own. Over time, that density becomes its strength.

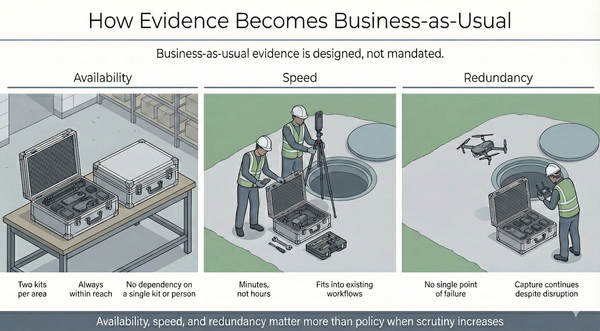

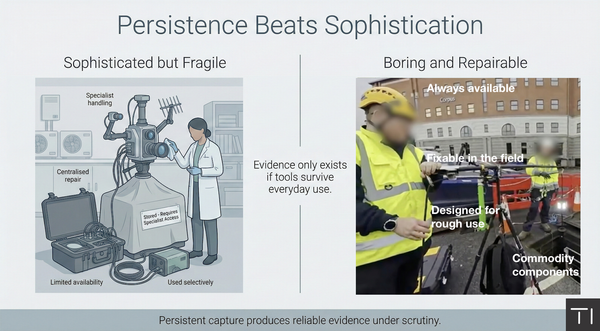

Ordinariness is what enables this. When capture tools are simple, repairable, and readily available, they are used more often. When a tripod can be fixed in the field, when cords and carabiners are commodity items, and when cameras are designed to survive rough handling and wet environments, capture stops feeling precious. It becomes part of the job, not an interruption to it.

The same applies to process. When capture takes minutes rather than hours, when it does not require traffic management or specialist permissions, and when it can be done by anyone already visiting the asset, the marginal cost of one more piece of evidence collapses. At that point, the decision is no longer whether to capture, but whether there is any reason not to.

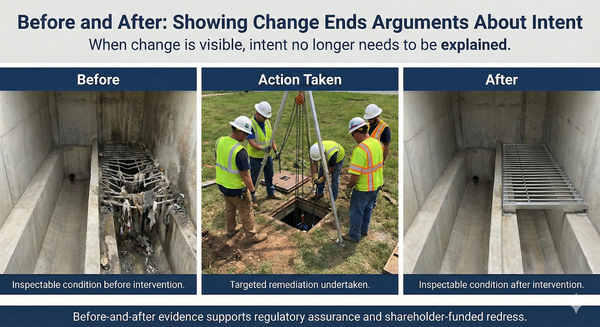

This is where evidence density starts to matter more than evidence perfection. A single, meticulously planned survey may provide high-quality information about one aspect of an asset. A large volume of routine, high-resolution visual context provides something different. It reveals patterns. It shows how conditions evolve. It exposes discrepancies between records and reality. It makes before-and-after states trivial to document.

Under regulatory and assurance pressure, this density is invaluable. Questions rarely arrive in the exact form anticipated when evidence was commissioned. They evolve. They compound. They return months later from different audiences. Evidence that was gathered once, for one purpose, often cannot stretch to answer them. Ambient evidence can.

There is also a governance effect. When evidence is exceptional, it tends to be owned by the team that commissioned it. When evidence is ambient, it becomes organisational. It is not tied to a particular project, individual, or decision. It is simply there, available to be inspected when needed. This reduces reliance on memory, explanation, and narrative continuity.

Importantly, this does not mean that specialist surveys lose their value. It changes their role. Surveys become confirmatory rather than exploratory. They are used to answer precise questions that ambient evidence has already surfaced, rather than to discover basic facts under time pressure. The overall evidence base becomes more robust, not less.

In the current regulatory environment, where enforcement timelines are compressed and scrutiny is intense, this distinction matters. Ofwat is no longer accepting “we thought we knew” as a sufficient basis for decision-making. Evidence needs to exist before the question is asked, not be commissioned after it arises. Ambient evidence makes that possible.

The strength of this approach lies in its ordinariness. Nothing about it relies on rare expertise or fragile processes. It works because it fits into the flow of everyday operations. Over time, it changes what is considered normal to know about an asset.

When evidence becomes ambient, it stops being something organisations scramble to produce under pressure. It becomes part of how the system sees itself. And in a sector where confidence under scrutiny now depends on what can be shown, not what is believed, that shift is decisive.