The Hidden Cost of Evidence Gaps in DWMP Delivery

UK water utilities spend a great deal of time discussing cost efficiency, delivery risk, and regulatory compliance. Far less time is spent asking a simpler question: what does it cost when evidence is not trusted?

In Drainage and Wastewater Management Plan (DWMP) delivery, lack of trust rarely stops work outright. Instead, it creates more of it. Assumptions are challenged repeatedly, submissions are expanded, site access is revisited, and contingencies grow. These activities are rational responses to uncertainty, but together they form a significant, often unmeasured, operational burden.

The costs show up in familiar places. Restricted-entry surveys are commissioned to confirm details that were assumed earlier. Internal teams make repeated visits to answer slightly different questions at different stages. External specialists are brought in to provide independent confirmation. Assurance cycles lengthen as reviewers ask for more context, more justification, and more evidence. Each step adds time, coordination effort, and expense.

Because these costs are distributed across teams and budgets, they are rarely seen as a single problem. Operations carry the burden of access and safety coordination. Asset strategy absorbs the cost of additional surveys and rework. Programme managers manage delay and scope change. Assurance teams handle extended challenge cycles. No single line item captures the cumulative impact of evidence gaps.

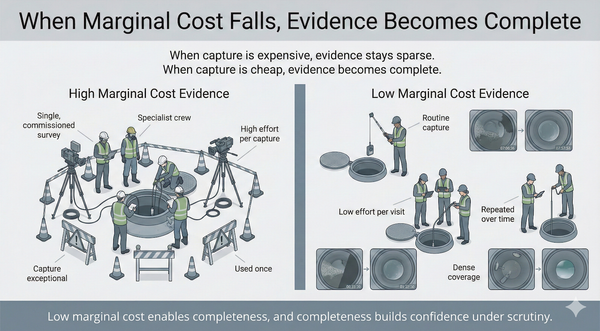

A simple comparison helps to make this visible. Consider the difference between a single, restricted-entry survey commissioned to answer a narrow question and the reality that often follows. That survey may need to be repeated because the evidence is not reusable. Internal teams may still visit the site to clarify access or condition. Designers may request additional confirmation when drawings do not align with what is expected. What appears as one discrete cost becomes a sequence of related activities, each justified on its own, but collectively expensive.

The effect is amplified when trust is low. If regulators, assurance teams, or local authority stakeholders are sceptical of the evidence presented, the response is not rejection but escalation. More detail is requested. More assumptions are tested. More conservative positions are taken. This is not adversarial behaviour; it is a predictable response to uncertainty. But it has a multiplier effect. Lack of trust does not halt progress. It multiplies the work required to achieve it.

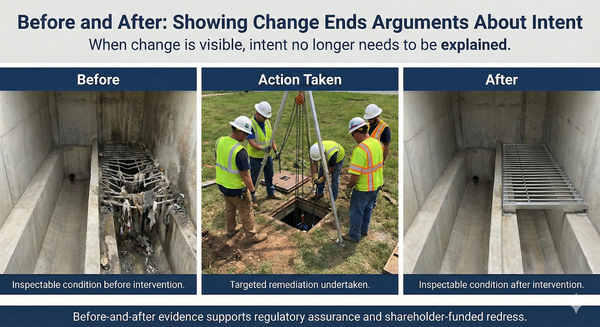

This is where transparency becomes an operational issue rather than a communications one. Public relations campaigns, stakeholder messaging, and engagement exercises have their place, but they do not resolve the underlying cause of mistrust. Trust is rebuilt when decisions can be shown, not just explained. When evidence can be inspected directly, revisited over time, and shared across organisations, challenge becomes more focused and proportionate.

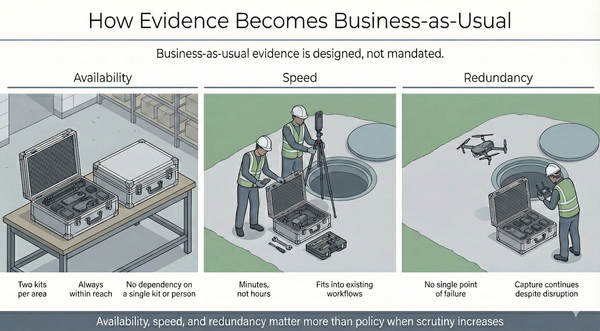

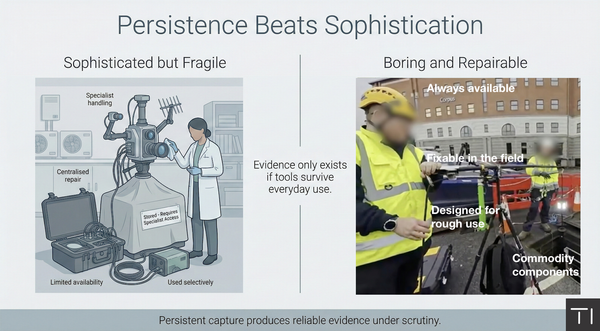

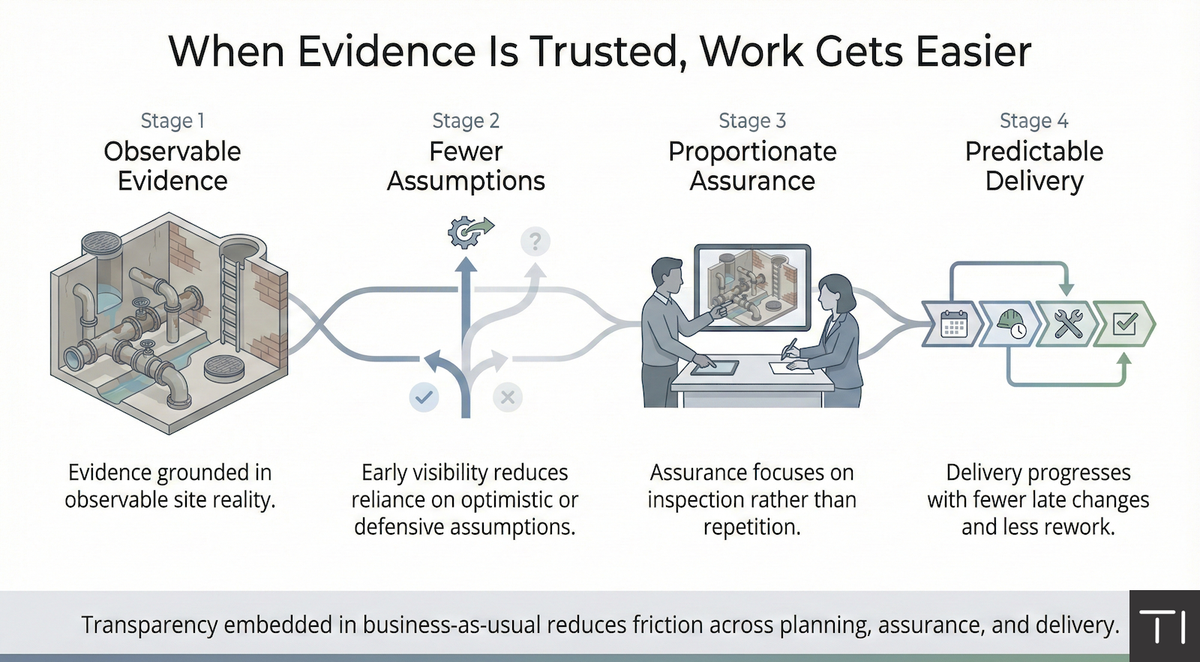

Embedding transparency into business-as-usual operations changes the economics. When observable site context is available early and remains accessible, fewer surveys are needed to confirm basic facts. Internal teams spend less time rediscovering what was already known. Assurance relies less on repetition and more on inspection. Over time, reality capture and shared evidence become part of the normal operating model rather than exceptional events commissioned under pressure.

This shift does not eliminate surveys or site visits altogether. Some questions will always require physical inspection. What changes is the default. Surveys become the exception rather than the rule. Engineers design and optioneer using evidence that already exists. Asset maintenance priorities are set with clearer understanding of condition and access. The cumulative effect is a reduction in rework, delay, and exposure.

There is also a longer-term benefit that is harder to quantify but equally important. When evidence is trusted, relationships improve. Regulators spend less time challenging and more time engaging constructively. Local authorities gain confidence that decisions are grounded in reality. Customers are more likely to accept outcomes when the rationale can be demonstrated clearly. Trust is rebuilt not through messaging, but through consistent, observable practice.

The real question for utilities is therefore not how much a new capability costs, but how much work is being done today because evidence is not trusted. How many additional surveys, reviews, and assurance cycles are driven by gaps that could have been closed earlier? And how much of that effort would simply disappear if transparency were part of BAU rather than an exception?

Seen in this light, improving evidence quality is not an innovation initiative. It is a way of reducing friction that has become normalised. The benefits may be hard to pin down to a single number, but they are felt daily across planning, operations, and assurance. Making those costs visible is the first step toward reducing them.