The Asset Visibility Gap: Why Ofwat Is No Longer Accepting “We Thought We Knew”

Across the UK water sector, enforcement activity has converged on a single underlying failure. Companies have not lacked intent, investment, or analytical capability. What they have lacked is reliable, inspectable visibility into the condition and configuration of their assets. Ofwat’s recent actions make clear that this is no longer treated as a peripheral weakness. It is now a regulatory fault line.

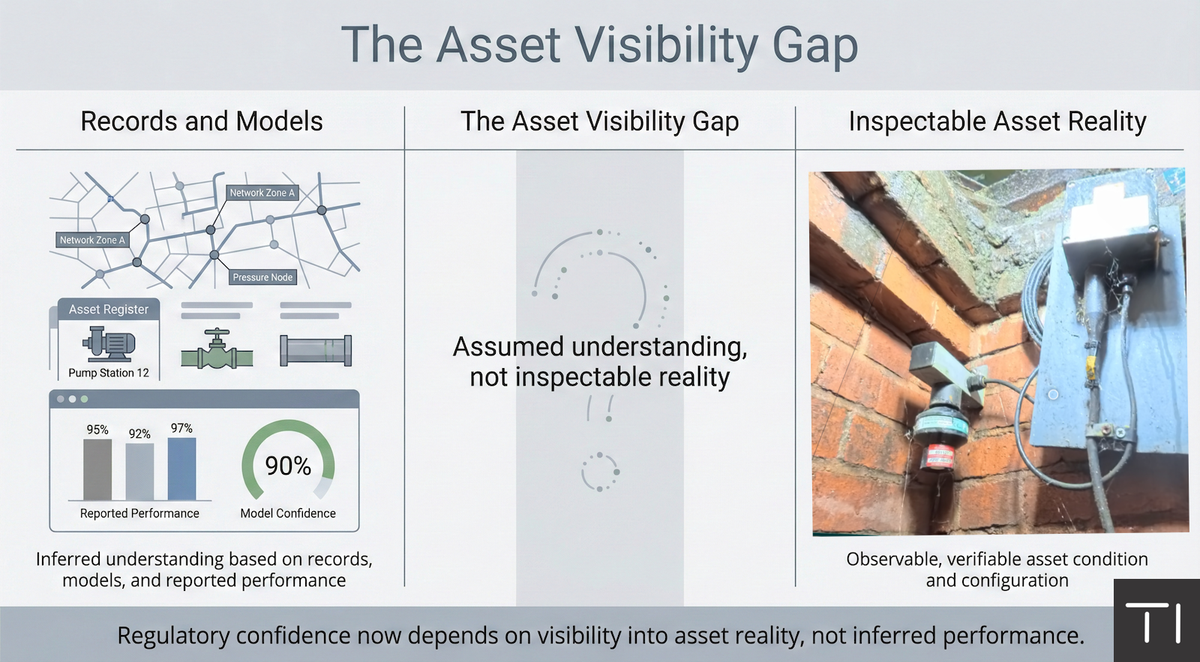

This shift is important. For many years, asset understanding was inferred from records, models, and performance indicators. These tools remain essential, but they were often asked to stand in for direct knowledge of what exists on site. When outcomes aligned with expectations, this approach held. Under scrutiny, it has not.

The gap that has opened up is not between data and decisions, but between records and reality. Asset registers describe what should be there. Models estimate how assets should behave. Reports summarise what teams believe is happening. What has been missing is a consistent, shared way to see what is actually there, in enough detail to withstand challenge.

Ofwat’s enforcement actions reflect this. Failures cited across the sector consistently point to inadequate data gathering, processes not fit for purpose, and insufficient line of sight for senior management. These are not isolated operational issues. They are symptoms of a systemic visibility gap, where organisations are required to make and defend decisions about assets they cannot reliably inspect without returning to site.

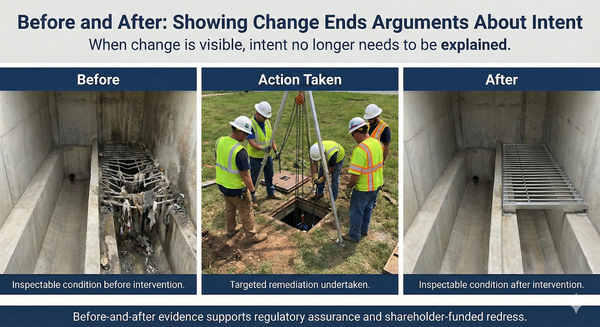

This is why “we thought we knew” is no longer an acceptable position. Under enforcement, assumptions are tested. When evidence is indirect or abstract, challenge cycles lengthen and confidence erodes. The regulator’s response has been to demand remediation plans, board-level oversight, and demonstrable control. At the core of each requirement is the same expectation: asset understanding must be grounded in evidence that can be inspected, not inferred.

The distinction matters. Records and models are designed to abstract. They compress complexity to make networks manageable at scale. That abstraction is powerful, but it comes at a cost. When physical configuration, access constraints, or condition deviate from what records suggest, the divergence often remains hidden until it becomes operationally or environmentally significant. At that point, response is reactive, expensive, and difficult to defend.

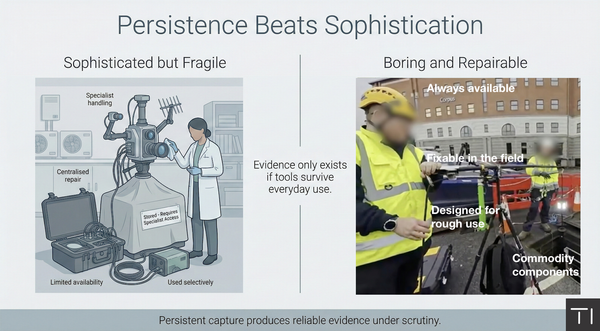

Experienced water professionals recognise this immediately when they see rich site context. High-dimensional visual evidence triggers rapid pattern recognition. Congestion, unexpected connections, dry pipes, construction era, and signs of degradation are understood at a glance. This is not intuition replacing analysis. It is expertise finally being given the information it needs to operate properly.

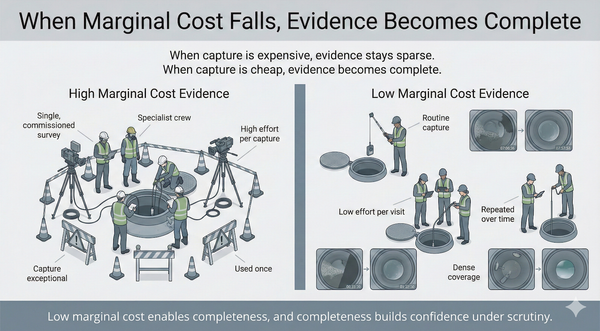

The absence of that visibility has a measurable cost. Evidence gaps drive repeat site visits, external surveys, conservative assumptions, and extended assurance cycles. They also undermine trust. When regulators, boards, or external reviewers cannot inspect the basis for decisions, uncertainty is priced in through buffers, haircuts, and delayed approvals. The work multiplies, not because anyone is acting unreasonably, but because uncertainty has not been resolved early enough.

What Ofwat is now signalling is that this state of affairs is no longer tolerable. Visibility into asset reality is being treated as a regulatory baseline, not an optional enhancement. Boards are expected to have line of sight. Remediation plans are expected to be grounded in verifiable root causes. Funding requests are expected to demonstrate that spend targets what is actually wrong, not what models suggest might be wrong.

This is not a demand for more reporting. It is a demand for better evidence. The regulator is not asking companies to explain their assets more persuasively. It is asking them to show them.

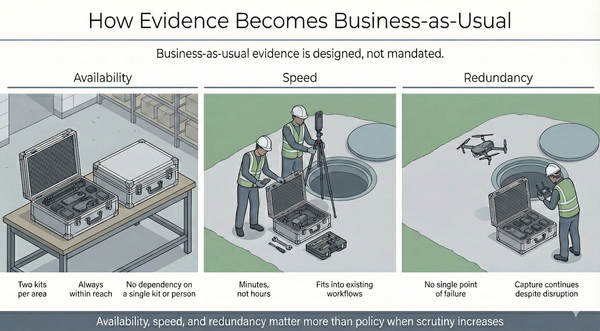

Seen in this light, the asset visibility gap is not a technology problem. It is a governance problem. When organisations rely on indirect representations of reality, they create fragility under scrutiny. When they normalise inspectable, revisitable evidence as part of business as usual, they reduce friction across operations, assurance, and delivery.

The implications extend beyond compliance. Visibility that satisfies the regulator also supports earlier risk identification, more confident option selection, and fewer late-stage surprises. It reduces the hidden cost of mistrust and shortens the distance between knowing and acting.

Ofwat’s enforcement activity has simply made this explicit. The era in which asset understanding could be assumed from records alone has ended. Visibility into reality is now a prerequisite for regulatory confidence. Utilities that close the asset visibility gap will find that many other problems become easier to manage. Those that do not will continue to discover that “we thought we knew” is an increasingly expensive position to defend.