From Records to Reality: Why Evidence Quality Matters More Than Data Volume

Over the past decade, UK water organisations have invested heavily in data. Asset registers have become more complete, data warehouses more sophisticated, and analytics more deeply embedded in planning and reporting processes. In many respects, data maturity has become a proxy for organisational capability.

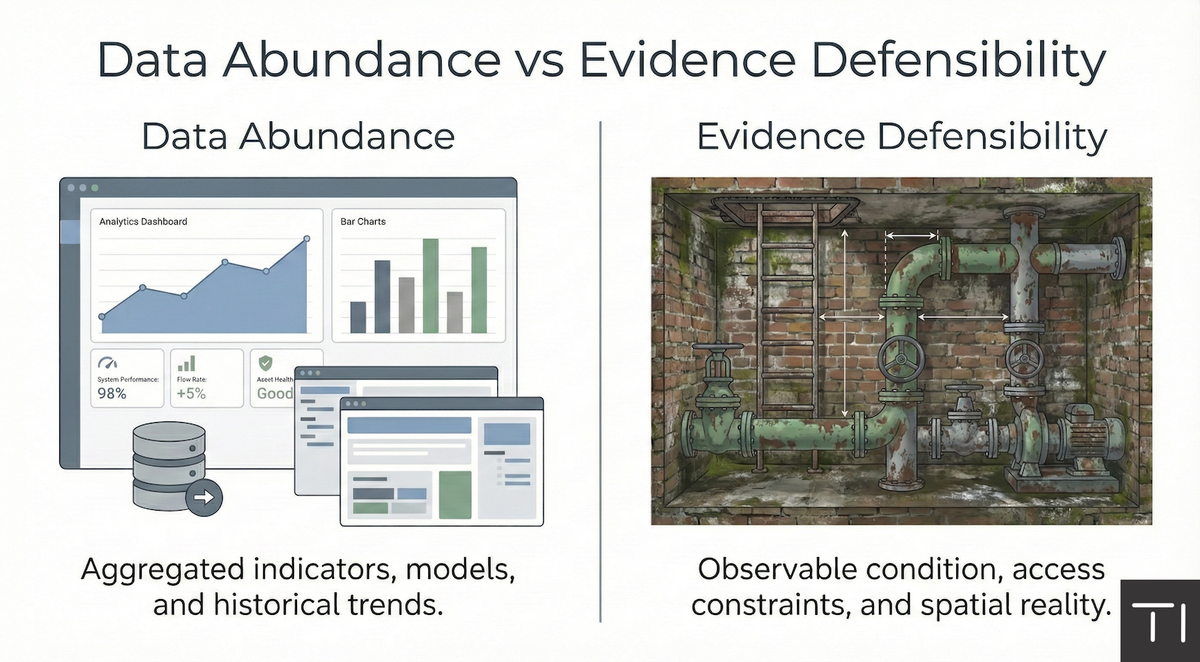

Yet when Drainage and Wastewater Management Plan (DWMP) assumptions are challenged, a familiar pattern often emerges. Teams can point to models, metrics, and historical trends, but struggle to provide direct, observable evidence that explains how those assumptions relate to current site conditions. The issue is not that data is missing. It is that much of the available data is abstracted away from the physical reality it is meant to represent.

This is not a flaw in data platforms. It is a consequence of what they are designed to do. Data warehouses and analytics systems aggregate, standardise, and summarise information across large asset bases and long time horizons. They are optimised for consistency, comparison, and trend analysis. In doing so, they necessarily remove detail, context, and spatial nuance.

For many DWMP questions, that abstraction is entirely appropriate. Long-term performance trends, capacity modelling, and investment prioritisation depend on it. However, assurance and challenge increasingly focus on a different layer of the problem. Regulators and internal reviewers are asking whether specific assumptions hold true in specific places, under specific constraints. At that point, the distance between aggregated indicators and physical reality becomes visible.

Abstract indicators struggle to answer practical questions. A performance metric can indicate deterioration, but not whether corrosion is accessible or obscured. A capacity model can identify a bottleneck, but not whether there is space to install additional equipment. A risk score can highlight a concern, but not whether site access or configuration makes intervention feasible within the proposed timeframe.

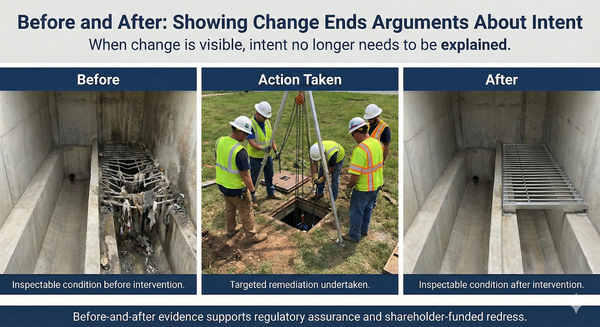

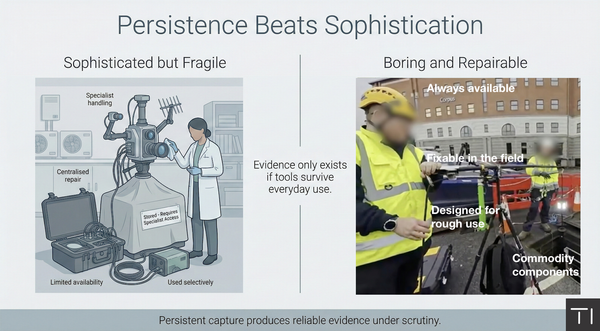

When these questions arise, teams often return to drawings, photographs, and site visits to fill the gaps. Drawings may reflect design intent rather than current condition. Photographs may be outdated or captured without measurement or spatial reference. Reports may summarise findings that cannot easily be revisited or interrogated once the context has faded. Each of these artefacts provides partial evidence, but rarely a complete or reusable view.

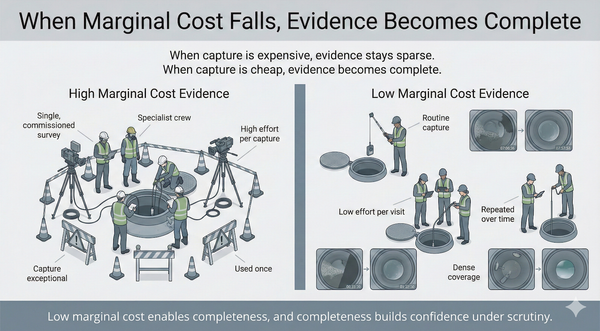

Under increasing regulatory scrutiny, the quality of evidence matters as much as its existence. Assurance is not only about demonstrating that analysis has been performed, but that assumptions can be traced back to something observable. Evidence that can be revisited, interrogated, and shared carries more weight than static outputs that rely on trust in prior interpretation.

Visual and spatial evidence plays a particular role here. Being able to see how assets are arranged, how space is constrained, and how condition manifests in the field allows challenge cycles to shorten. Questions that might otherwise trigger a site visit or prolonged debate can often be resolved by reference to a shared view of the asset. This does not replace modelling or analysis, but it grounds them.

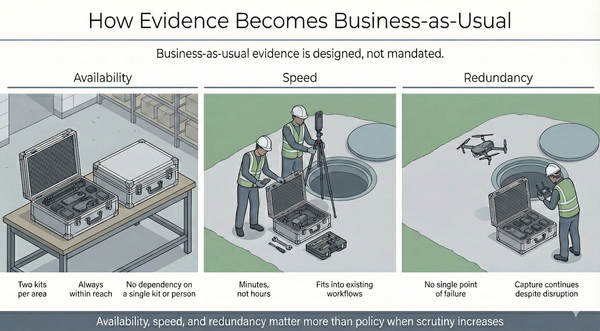

Crucially, strengthening evidence quality does not require changing existing systems of record. Warehouses, GIS platforms, and asset management systems remain essential. What changes is the ability to connect those systems to observable context at the point where decisions are made. When records can be linked to evidence that shows how assets actually exist on site, assumptions become easier to defend and easier to challenge.

From a DWMP perspective, this distinction between data volume and evidence quality is becoming more important. Decisions are increasingly scrutinised not just for internal consistency, but for their traceability to real-world conditions. Evidence that exists only as an abstract indicator or a static report is harder to defend than evidence that can be revisited and understood by different audiences over time.

The implication is subtle but significant. Maturity should not be judged solely by how much data is held or how tightly systems are integrated, but by how confidently decisions can be tied back to observable reality. When evidence exists at decision time, and assumptions can be traced to what can actually be seen and understood on site, both delivery risk and assurance burden are reduced.