Due Diligence Is an Evidence Stress Test

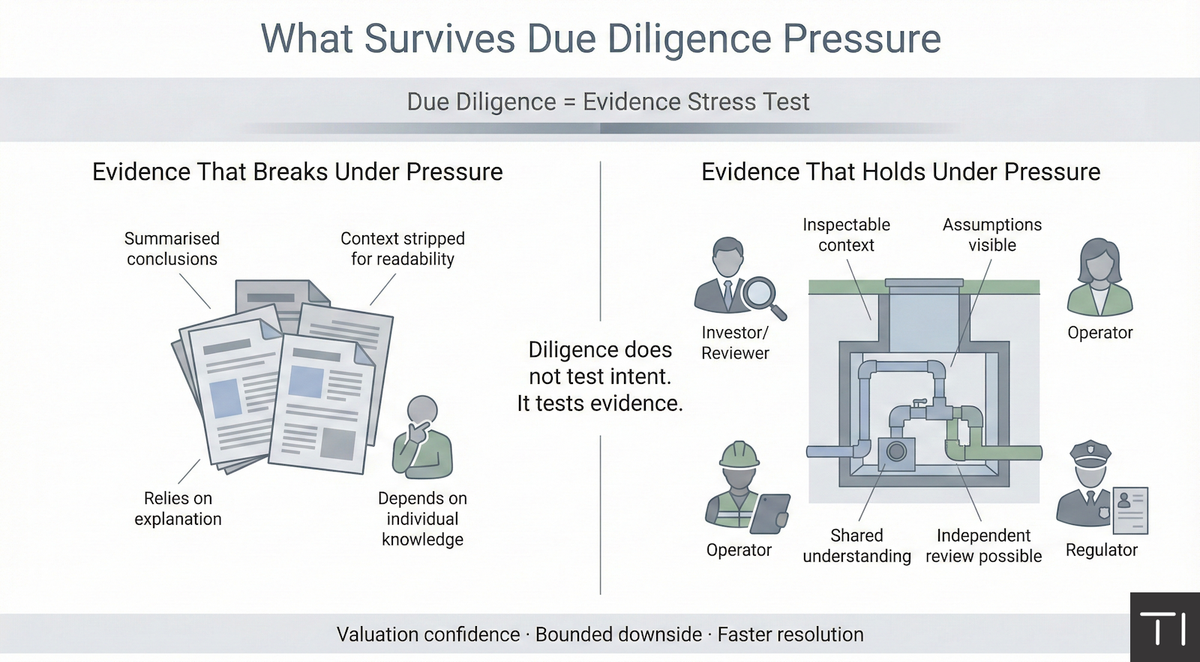

Due diligence is where comfortable assumptions meet pressure. It is not designed to validate what is already believed, but to expose what might go wrong. In that sense, it functions as a stress test for evidence. What survives scrutiny under time constraint, adversarial questioning, and third-party review is treated as reliable. What does not is discounted, deferred, or priced as risk.

This is why evidence that appears adequate in business-as-usual contexts often breaks down during diligence. Internal reports, summaries, and historic analyses are usually produced to inform decisions, not to withstand challenge. They work well when the audience shares context and institutional memory. They are far less effective when examined by people who do not.

Static reports are particularly vulnerable. They present conclusions without preserving the context that produced them. When a diligence team asks how a judgement was reached, or what alternatives were considered, the report itself rarely contains enough information to answer. Follow-up questions trigger a search for supporting material, explanations from individuals, or fresh site visits. Each step introduces delay and uncertainty.

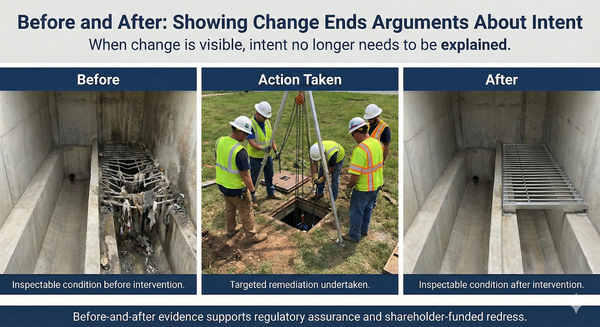

Inspectable context behaves differently. When evidence allows reviewers to see how assets are arranged, how condition presents, and how constraints interact, many lines of questioning resolve quickly. Inspectable evidence does not eliminate judgement, but it anchors it. Reviewers can test assumptions directly rather than probing the narrative built around them.

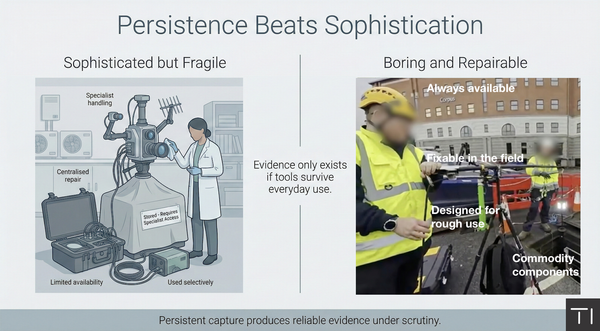

Person-dependent knowledge is another common failure point. In many organisations, confidence rests on the experience of a small number of individuals who know the assets well. Statements such as “we’ve always managed it” or “it’s never been a problem” may be entirely true, but they are fragile under diligence. When those claims cannot be substantiated by shared, revisitable evidence, they lose weight quickly.

Diligence teams are not dismissing experience; they are testing transferability. If understanding exists only in someone’s head, it cannot be relied upon once ownership, governance, or personnel change. Shared evidence turns individual knowledge into organisational knowledge. Without it, even well-run operations appear riskier than they may actually be.

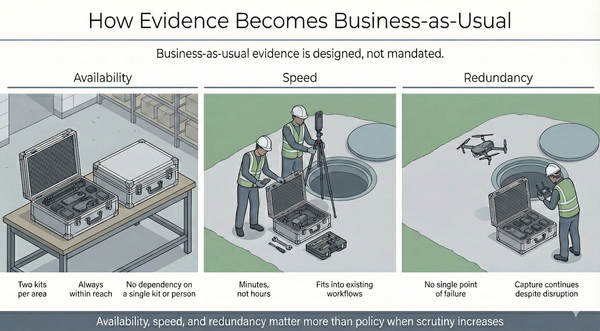

Time pressure amplifies these weaknesses. Diligence rarely unfolds at a comfortable pace. Requests arrive quickly, priorities shift, and questions evolve as new information emerges. Evidence that requires explanation, reconstruction, or translation struggles to keep up. Evidence that can be inspected directly scales much better under this pressure.

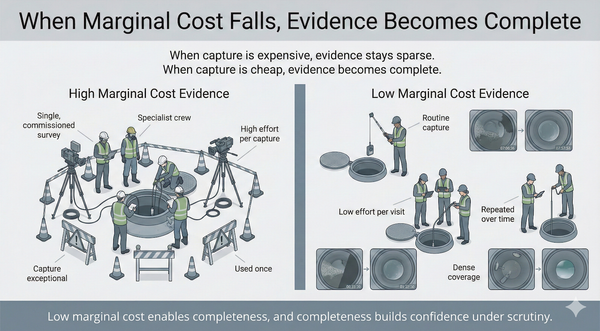

This is why indirect evidence collapses under scrutiny. It is not that it is wrong, but that it is incomplete. Summaries compress complexity. Assumptions are hidden to keep reports readable. Context is stripped away to make documents concise. These are sensible choices for internal use. Under diligence, they become liabilities.

The implicit lesson is straightforward. Evidence intended to support valuation, refinancing, or regulatory review must be able to survive hostile questioning. It must stand on its own, without relying on personal authority or lengthy explanation. It must allow third parties to see enough of reality to bound uncertainty for themselves.

Due diligence does not require perfection. It requires defensibility. Assets supported by inspectable, shared evidence tend to withstand pressure even when challenges are raised. Assets supported only by narratives and historic reports tend to attract buffers and discounts, regardless of how well they have been managed to date.

In this sense, diligence is not unfair. It is simply unforgiving. It reveals whether evidence has been designed to inform decisions, or to endure scrutiny.