Why Integration Slows Operational Insight Before It Speeds It Up

UK water utilities operate some of the most mature digital estates in the infrastructure sector. Geographic information systems, asset management platforms, enterprise resource planning tools, document repositories, and data warehouses are widely deployed and deeply embedded. In most organisations, the problem is not the absence of systems.

The challenge lies in how those systems relate to day-to-day operational reality.

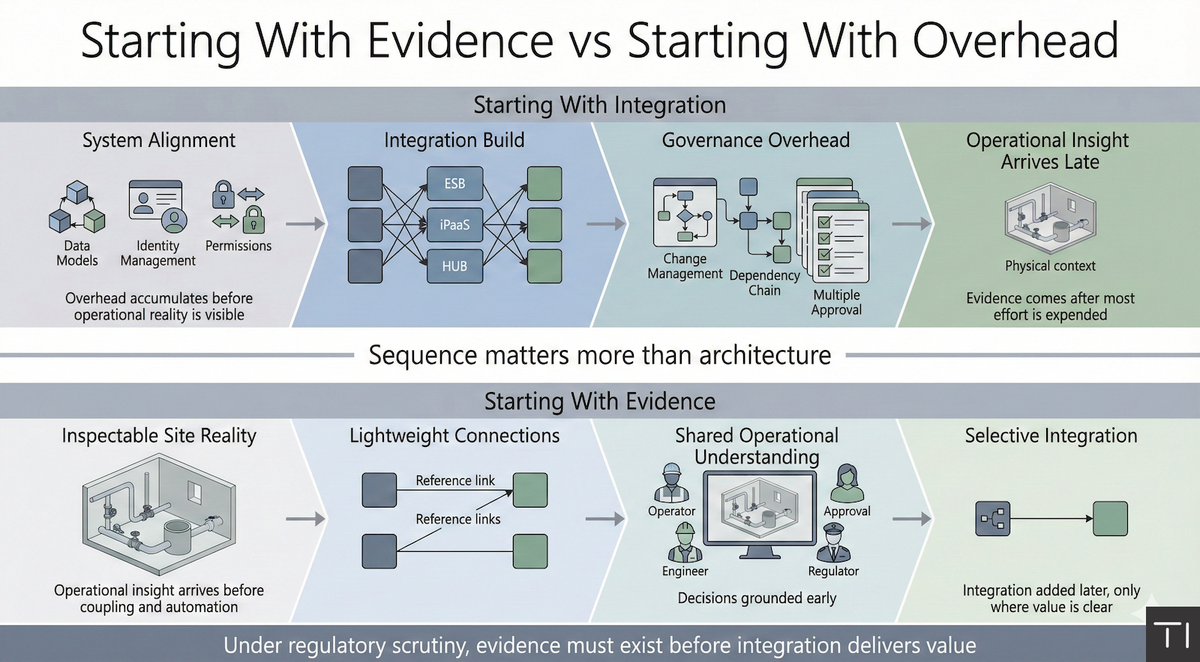

When uncertainty arises about the condition of an asset or the feasibility of a piece of work, the instinctive response is often to connect systems more tightly. More integration promises consistency, automation, and a single source of truth. In practice, the “single source of truth” arrives late—often too late to help when the uncertainty is most acute.

This is not because integration architectures are misguided. Integration hubs, enterprise service buses, and integration platforms exist for good reasons. They support governance, standardisation, and scale. However, they also impose requirements that are difficult to satisfy early in an operational use case. Data models must be aligned. Identities and permissions must be coordinated. Changes in one system ripple through others. Each step is reasonable in isolation. Together, they slow delivery.

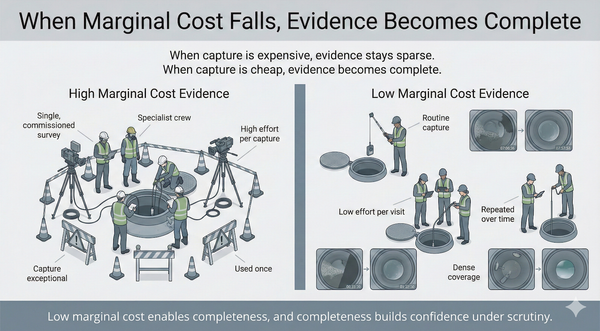

For operational questions, this sequencing matters. Understanding whether an asset can be accessed safely, whether pipework is congested, or whether deterioration is visible does not usually require tightly coupled systems. Yet integration programmes often begin before those basic questions are resolved. Overhead arrives first, while insight arrives later.

The same tension appears in analytics and warehousing. Data warehouses and lakehouses play an essential role in regulatory reporting, performance analysis, and long-term planning. They are designed to aggregate and abstract information over time. That abstraction is deliberate and valuable. It is also the reason these systems struggle to answer certain operational questions.

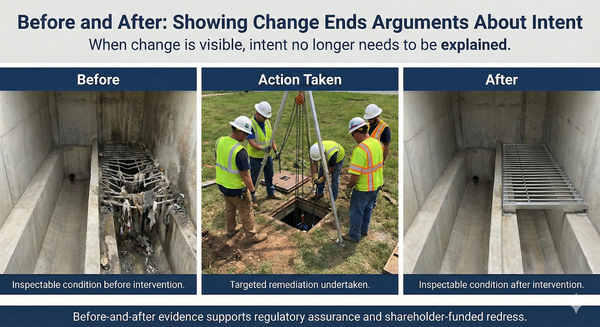

A warehouse can show that an asset exists, how it is categorised, and how it has performed historically. It cannot show how that asset is arranged in space, whether access is constrained, or whether condition has changed in ways that matter for intervention. When those questions arise, teams fall back on drawings, photographs, and site visits or surveys that can take weeks to arrange and complete. A gap opens between reporting truth and field truth.

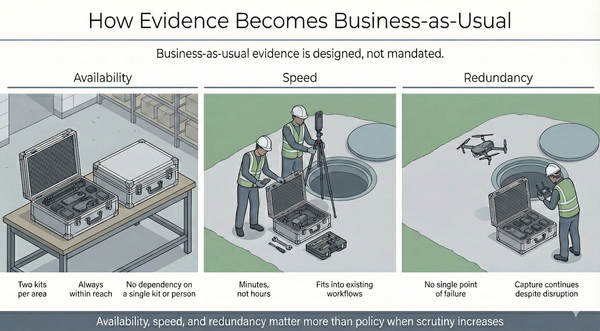

What changes outcomes is not replacing these systems, but changing the starting point. Instead of moving and transforming data between platforms, some utilities are focusing first on accessing operational reality and making it inspectable where decisions are made. In this approach, existing systems of record remain authoritative for their data. What is added is a way to reference observable site context directly, without duplicating or reshaping it.

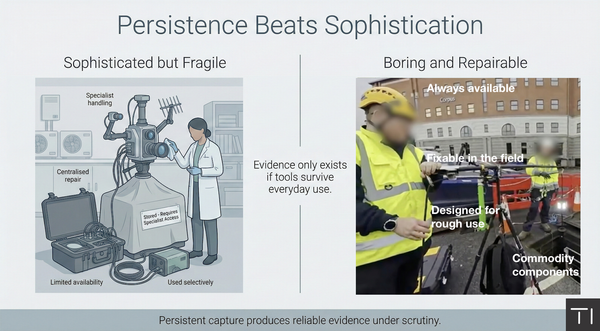

Simple linking patterns are sufficient for this. A stable reference from an asset record or work order to captured site reality connects systems without coupling them. There is no shared schema, no write-back, and no requirement to synchronise models. Because the link is a reference rather than a dependency, it can be created quickly and removed without consequence.

When this is combined with high-dimensional site evidence, the effect is immediate. Visual records of physical sites, such as 360-degree imagery or photogrammetric views, allow teams to see and understand conditions remotely. Engineers, planners, and safety specialists can interrogate the same evidence from their own systems, without waiting for integration projects to complete or for repeat site access to be arranged.

The practical consequences are predictable. Deployment is faster because it does not depend on large IT programmes. Governance risk is lower because system boundaries are preserved. Evidence captured once can be reused across maintenance planning, capital scoping, safety review, and assurance. Decisions can be traced back to observable conditions rather than inferred states.

This does not remove the need for integration. It repositions it. Once workflows are understood, value is demonstrated, and data requirements are clear, selective integration can add automation and efficiency. Warehouses continue to support reporting and trend analysis. Integration hubs continue to coordinate systems where real-time interaction is genuinely required.

What changes is the sequence. By starting with inspectable reality and lightweight connections, utilities avoid committing early to heavy coupling before they understand what actually needs to be seen, shared, or automated. Integration becomes an optimisation step rather than a prerequisite.

In the current regulatory environment, this sequencing is no longer a matter of preference. Ofwat’s recent enforcement actions show that companies need to have robust evidence in place before regulators—or incidents—put it to the test. Operational insight is required early, often under time pressure. Approaches that begin with complexity struggle to keep up. Approaches that begin with visibility have a chance to respond proportionately.

The choice is not between integration and no integration. It is between starting with evidence or starting with overhead.